Happy Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

Dr. Martin Lurther King, Jr. was a man of honor, kindness, and intellect. He helped to bring a new age within America and his teachings are still impactful in today’s fight for equality. And while it’s sad that we still have to protest for Black Lives, with many still pushing back, we wouldn’t even be at this point if it weren’t for MLK.

But even Dr. King needed help and advice. Almost no one climbs a mountain on their own, after all. So who were some of the most impactful advisers and influences in MLK’s life? Surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, there were several gay Black men who impacted Dr. King just as much as he impacted us. And here are a few of those names and faces.

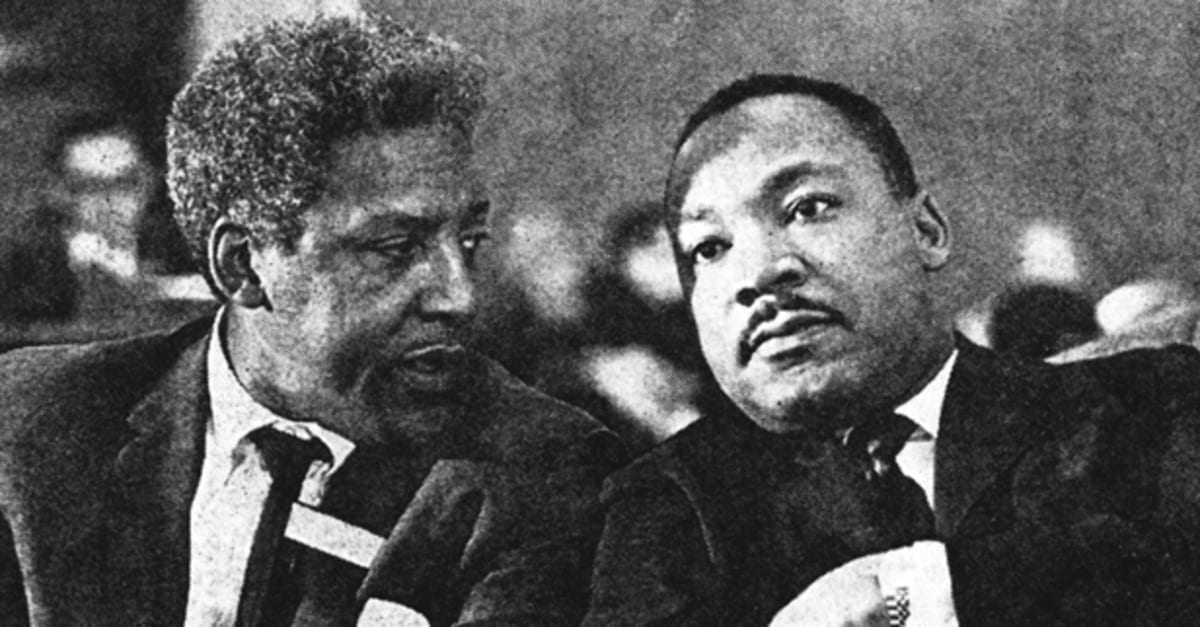

Bayard Rustin

Social justice activist and organizer Bayard Rustin was considered one of Dr. King’s most trusted advisers. At one point, MLK considered Rustin as not only a mentor but also like a big brother. In fact, it’s believed that it was Rustin who introduced Mahatma Gandhi’s peaceful protest approach to Dr. King. In addition, Bayard Rustin organized the March on Washington and stood beside Dr. King as the leader gave his iconic “I Have A Dream” speech.

Rustin’s relationship with Dr. King was so impactful that conservative politicians plotted to create a rift between the two. Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. used Rustin’s arrest for having sex in a public car as an excuse to strong-arm Dr. King into ostracizing Bayard Rustin. That crime remained on Rustin’s record up until last year.

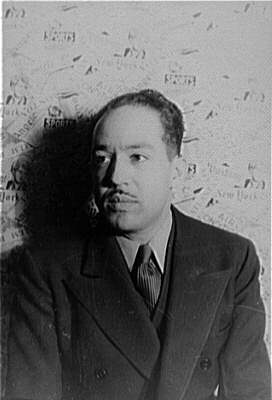

Langston Hughes

While Langston Hughes and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. did not openly seem close, historians believe the former man’s art had an influence on Dr. King’s speeches. As Smithsonian Magazine wrote in 2018, the two maintained a friendship through exchanging letters and even went on a trip to Nigeria together in 1960.

“Hughes’s poetry hovers behind Martin Luther King’s sermons like watermarks on bonded paper,” writes scholar W. Jason Miller in a post for The Florida Bookshelf.

Nine months before Dr. King gave the “I Have A Dream” speech next to Bayard Rustin, he gave the speech in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. But according to scholars, Dr. King had an earlier speech that touched on “the dream” concept before this iconic speech. On Aug. 11, 1956, Dr. King gave a speech called called “The Birth of A New Age.” At the end of that speech, many believe Dr. King rewrote Langston Hughes’ “I Dream a World” poem, “A world I dream where black or white / Whatever race you be / Will share the bounties of the earth / And every man is free.”

Many believe this was the precursor to Dr. King’s iconic speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial.

“I have a dream that one day,” he wrote. “Little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.”

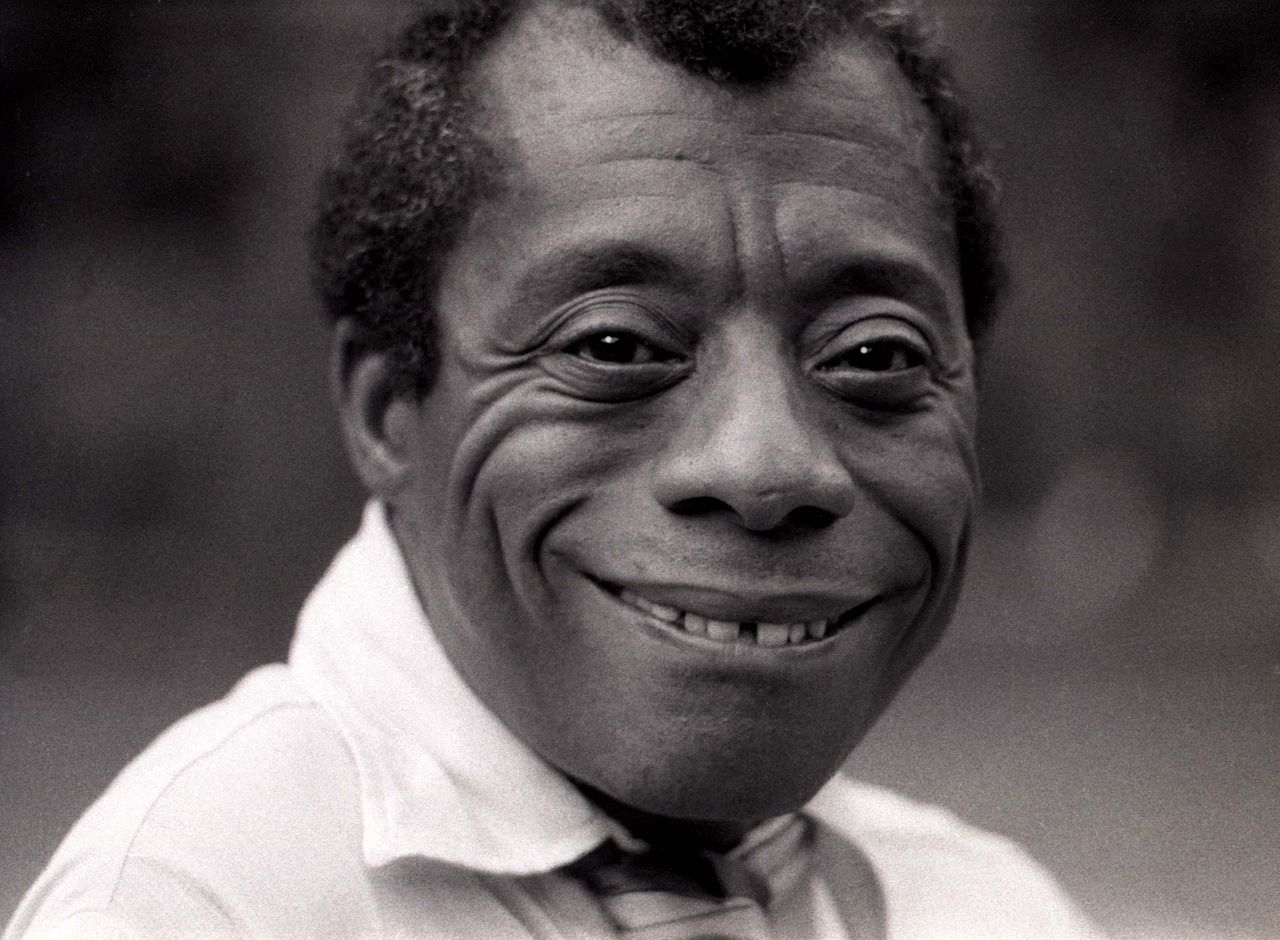

James Baldwin

But Langston Hughes wasn’t the only gay black writer to inspire Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Dr. King also knew the iconic James Baldwin.

Baldwin first met King in 1957, during the Atlanta stop of King’s tour of the American Deep South. Baldwin saw King deliver a sermon before conducting an interview with him for Harper’s magazine. Afterward, the two stayed in touch throughout their collective efforts to support the Civil Rights Movement.

“The effect of your work, and I might almost indeed, say your presence, has spread far beyond the confines of Montgomery, as you must know,” Baldwin wrote to Dr. King in a letter to set up the interview. “It can be felt, for example, right here in Tallahassee. I am one of the millions, to be found all over the world but more especially here, in this sorely troubled country, who thank God for you.”

Unfortunately, as with Bayard Rustin and Langston Hughes, a rift soon grew between the two. While King distanced himself from Hughes due to his ties towards communist organizations, Rustin and Baldwin lost connection with Dr. King because of their open sexual orientation. Despite that, Baldwin still recognized Dr. King’s influence on the movement and his personal life. Baldwin, who went to Dr. King’s funeral, noted that he tried to stay stoic in the face of his late friend and ally.

“I did not want to weep for Martin, tears seemed futile,” he later wrote. “I may also have been afraid, and I could not have been the only one, that if I began to weep I would not be able to stop.”

Long after Langston Hughes’ passing, it was believed more so by most ppl. that Hughes was gay, unlike Bayard Rustin & James Baldwin that were openly gay, since whatever Hughes’ sexual orientation was, Hughes evidently left it up to ppl. to perceive as to whatever they wanted to perceive.