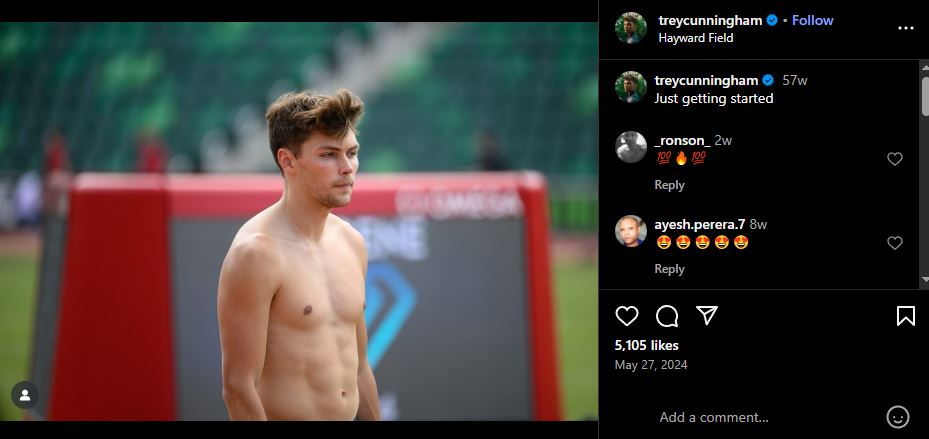

It took Trey Cunningham exactly thirteen seconds to storm through ten hurdles and etch his name atop the podium at the Paris Diamond League meet. But it took something more complex—and far less timed—for the professional hurdler to leap an internal barrier that had followed him for years: the decision to come out publicly as gay.

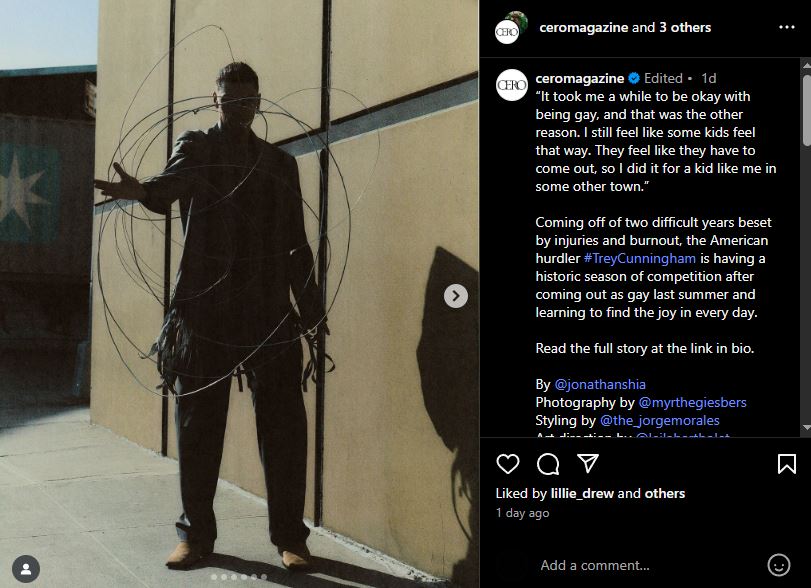

Since doing so in the summer of 2024, Cunningham hasn’t just been winning races—he’s been rewriting the rules of what success can look like for a gay man in elite men’s sports. It’s a story about authenticity, athleticism, and the quiet revolution that happens when someone decides to be fully themselves, no matter the stakes.

RELATED: Trey Cunningham Is Outrunning the Competition—and the Closet

“It was for me, just to be one hundred percent authentic, transparent, and not holding back any part of me,” Cunningham told Cero magazine. “My coach was really big on this, like, ‘You have to be totally confident in yourself and whatever that means to you on that track.’”

That confidence has translated into blistering results. After a disappointing 2024 Olympic Trials, Cunningham returned to the track with new fire—and results to match. In Miami’s Grand Slam Track meet, he swept the short hurdles, notched personal bests in the 110-meter hurdles and 100-meter sprint, and reclaimed his space among the world’s best. And in Europe, he’s kept the streak going, equaling his personal best at the Diamond League in Paris. A slump? Consider it officially hurdled.

But to suggest this resurgence is only about fast times would miss the bigger picture.

The Nerd Who Could Fly

Born in Winfield, Alabama, Cunningham doesn’t exactly fit the mold of your typical elite athlete. “I do not have the typical professional athlete story,” he admits. He grew up a self-described “nerd” who loved video games and books more than weight rooms or wind sprints—until seventh grade, when he tagged along with a cousin to track practice.

“I fell in love with it,” he says. “Also not the typical track story—I picked hurdles. You could say I do love throwing myself at solid objects for some reason at a high rate of speed.”

By high school’s end, Cunningham had run fast enough to earn a spot at Florida State University, where he majored in public relations and eventually earned a master’s degree in sports management. His thesis? A deep dive into burnout among athletes—a topic that hit far too close to home.

“I was sitting in my sports psychologist’s office and I was like, ‘I think I’m burnt out,’ and he’s like, ‘Yeah, I think you are too.’”

Even after winning silver at the 2022 World Championships, Cunningham couldn’t outrun a creeping exhaustion. A sport that rewards milliseconds often leaves its athletes drained for years.

But he’s never been a quitter. “I want to do well at what I want to do, and I’m lucky enough that I actually do love track and field,” he says. “I’ve got a good support team around me. They believed in me and didn’t really let me quit when I wanted to.”

That internal reboot—and the external support—gave him what he needed to rediscover joy in the grind. “I think finding that beauty in the process again was a big part of this year.”

Coming Out and Charging Forward

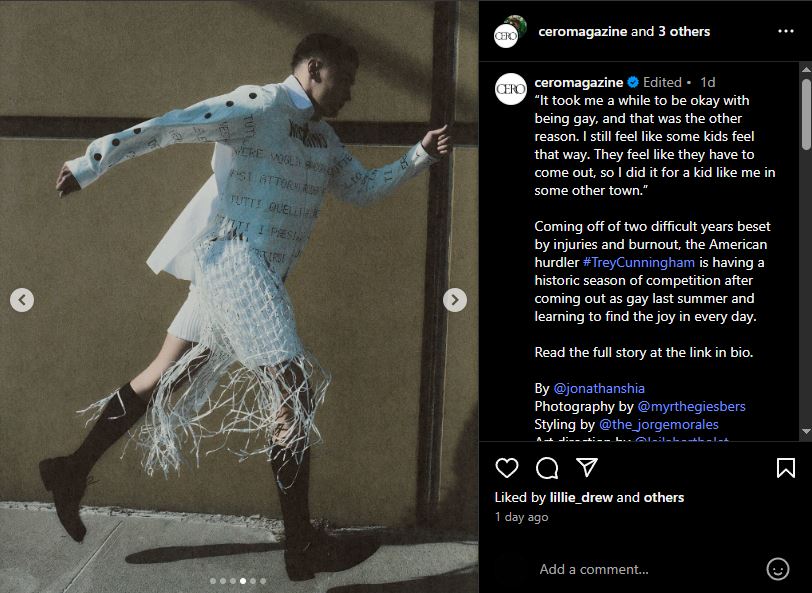

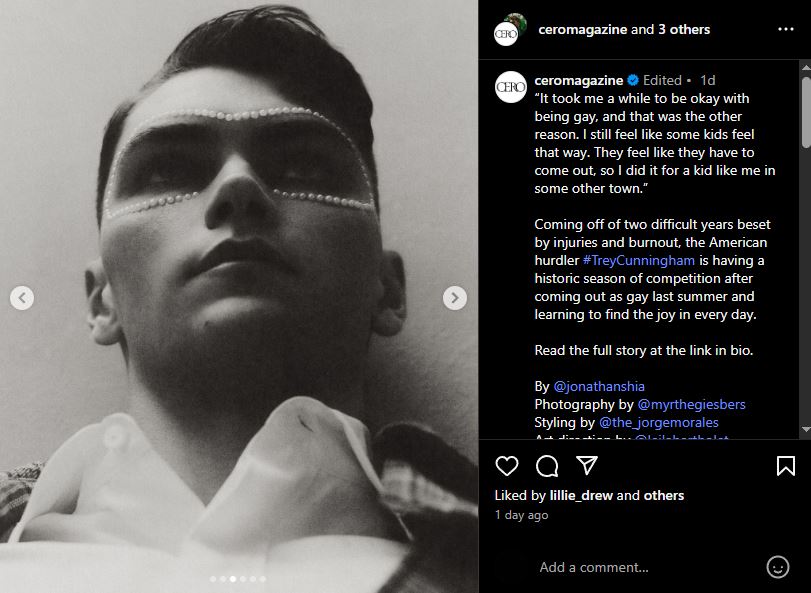

By the time he came out publicly via The New York Times, Cunningham had already shared the truth with friends and family. But the decision to go national was rooted in something bigger than just freedom—it was about visibility.

“We say our goals out loud. If there’s something we want to achieve, we say it. Putting something in words makes it real.”

He also wanted to unmask the idea that queerness and elite male athletics are somehow incompatible.

“There’s something incredibly powerful in being so authentic,” he told Cero. “A lot of people have told me that they appreciate me being around because I’m authentic. I’m always going to be truthful, I’m honest. I’m shooting it like it is and I’m being me.”

That authenticity didn’t just make Cunningham more comfortable—it made him faster. Or perhaps, it made the road clearer. Either way, the results speak for themselves.

He also acknowledges a sense of responsibility.

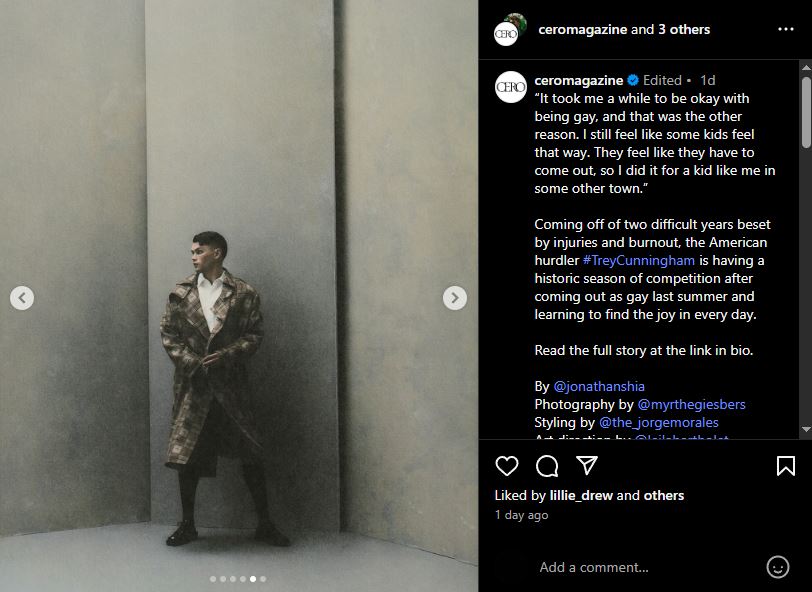

“It took me a while to be okay with being gay, and that was the other reason. I still feel like some kids feel that way. They feel like they have to come out, so I did it for a kid like me in some other town.”

Representation matters. Not just in the wins, but in the witness. Cunningham knows that a young kid might see his name in headlines, or his photo in a magazine spread, and recognize a possibility: that greatness and queerness can walk—no, sprint—the same path.

“It might not be the easiest at home if they’re younger, but when you get older, you get to decide who your family is, who you want to be around, who treats you nicely, who you allow in your space, and that’s hard for a lot of people to grasp.”

Running Toward the Future

At just 26, Cunningham has plenty of race left ahead. His eyes are firmly set on the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles, and his goals are as ambitious as ever: “best hurdler ever,” he says plainly. And after that? Maybe a PhD. Maybe a trailblazing new lane in sports psychology that finally addresses the inner lives of elite athletes. Whatever comes next, it’s clear Cunningham won’t be hiding from any part of it.

“We do sports because it’s a game. It brings us all together, it’s fun, that’s why you do it in the first place. I think that’s really helped me, trying to find the fun in everything, every single day has helped a lot.”

In a world that still too often tells LGBTQ+ athletes to shrink themselves, Trey Cunningham is running in the opposite direction—arms open, head high, proudly hurdling the idea that being gay is a disadvantage. In fact, in his case, it might just be his superpower.

And he’s not slowing down for anyone.

Source: Cero Magazine